Clarifying the Jurisprudence of the Kashmir Case

As of May 28, 2024, the jurisprudence surrounding the Kashmir issue remains complex. TheIndian government’s actions on August 5, 2019, including the abrogation of Articles 370 and35-A, and the subsequent affirmation of these actions by the Indian Supreme Court, do notoverride Article 103 of the UN Charter. This article prioritizes obligations under the UNCharter over other international agreements, which includes the jurisprudence developed fromthe August 1947 Standstill Agreement with Pakistan and India’s acceptance of accession inOctober 1947. Article 1(2) of the UN Charter and UN Security Council Resolution 91 establish an estoppelagainst any actions by India or Pakistan that could prejudice the equality of the people ofKashmir, their right to self-determination, or the conduct of a free and fair plebiscite under UNsupervision. Despite the significant changes and confusion following India’s actions in 2019,the Indian Supreme Court’s decision, and rumors of Pakistan’s possible annexation of AzadKashmir, it is crucial to understand the limits and possibilities of Indian and Pakistani controlover the region. This understanding hinges on the historical title and the evolving jurisprudencein the field. The source of Indian and Pakistani administrative controls over Jammu and Kashmir lies in theUN framework. The jurisprudence of the Kashmir case has expanded beyond the interests ofthe people of Kashmir and the Government of Pakistan to include the international community.On October 31, 1947, the Prime Minister of India sent a telegram to the Prime Minister ofPakistan, stating: “Our assurance that we shall withdraw our troops from Kashmir as soon as peace and order arerestored and leave the decision regarding the future of this State to the people of the State isnot merely a pledge to your Government but also to the people of Kashmir and to the world.” This assurance remains a significant element of the jurisprudence in the field. Therefore, theKashmir issue encompasses both pre-UN and post-UN components of international law anddiplomatic assurances, emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of the situation as itstands today. Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

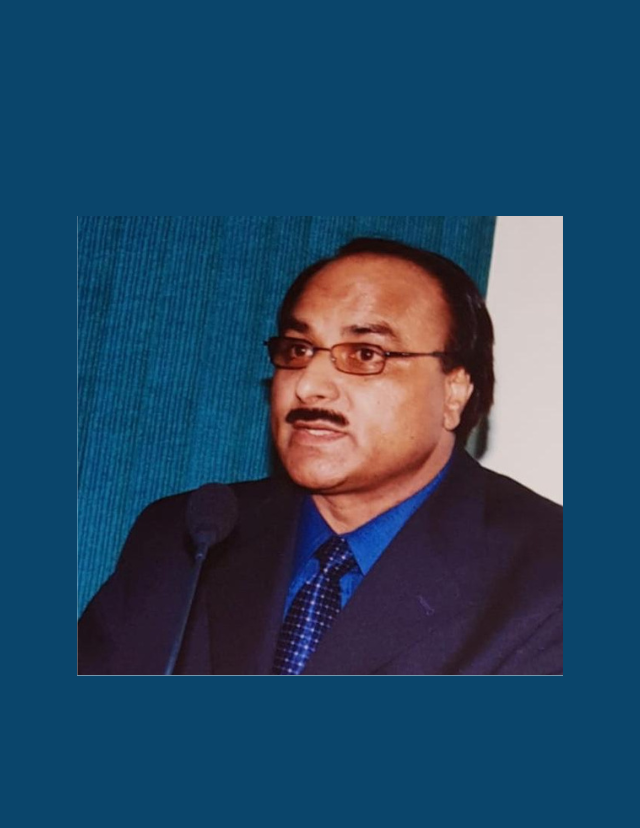

Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani

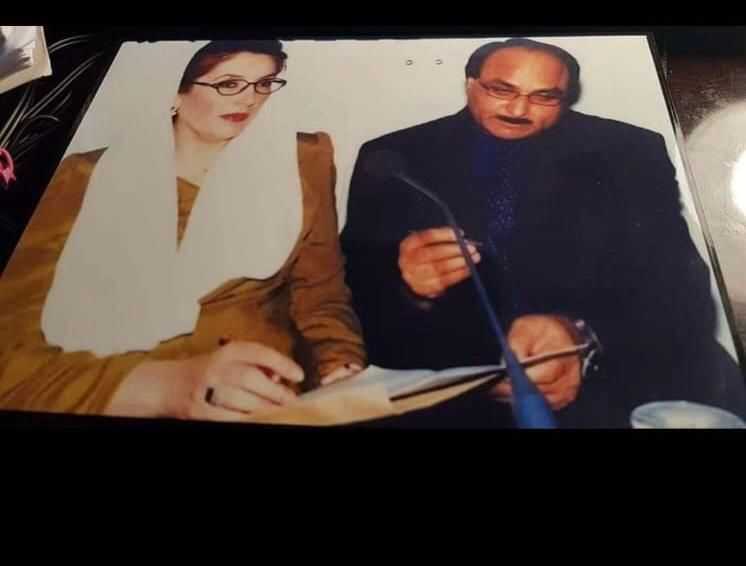

Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani hails from the historic village of Naranthal, also known as Jalsharee. The village sits on the banks of the river Jhelum. It is a modest geographical tributary of District Baramulla, Kashmir. Renowned for its Naranthal Temple and the refreshing Jalshree spring, the village shares its boundaries with two other villages Khadaniar (Khadniyar) and Drangbal, also known as Takisultan. The lineage of the Gilani family traces back to Baghdad, Iraq, journeying through Peshawar in British India and Lahore before settling in Khanyar, Srinagar, Kashmir, where they serve as Gaddi Nashin’s of the shrines of Dastgeer Sahib. Dr. Gilani’s educational journey traversed through the corridors of Government Middle School Khadniyar, Government Higher Secondary School Baramulla, and Degree College Baramulla. He pursued English Literature & Politics at the University of Kashmir, Law at S M Law College Karachi, Islamic Law at Kings College London, and International Law at Queen Mary University London. Additionally, his academic pursuits extended to Victimology at IUC Dubrovnik, in former Yugoslavia, and Peacekeeping/Humanitarian Operations & Election Monitoring in Pisa, Italy, under the 1996 UN and European Commission Programme. He stands as one of the select 40 individuals chosen under this esteemed program and holds a Ph.D. in the Jurisprudence of UN Resolutions and the Kashmir Case. His notable engagements include representing Unrepresented Peoples and Nations on the 33-member UN-NGO-Liaison Committee at the UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna (1993), where he also served on the UN-NGO Liaison Diplomatic Committee. Dr. Gilani addressed the Plenary and the Main Committee of the Conference, leaving an indelible mark with his insights. Begum Nusrat Bhutto from Pakistan and Atal Bihari Vajpayee from India, also addressed the Plenary and the Main Committee of the Conference on behalf of their respective countries. Dr. Gilani authored a chapter on Juvenile Justice in Saudi Arabia for a seminal work titled “Delinquency and Juvenile Justice in the Non-Western World,” providing invaluable insights for students, scholars, and practitioners. Acknowledged by the United Nations since January 1990, Dr. Gilani has lent his expertise to various international platforms, including the UN Commission for Human Rights, UN Sub Commission for Human Rights, UN Human Rights Council, Islamic Summit in Casablanca, and CHOGM-93. His commitment to promoting and safeguarding human rights transcends borders, evidenced by his diverse professional engagements, including roles at the Ministry of Information Government of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan Red Cross, Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation, and the UNHCR/UKIAS Refugee Section in London. He became the first Muslim Director of Millan Asian Centre in London and was elected on the General Council of UKIAS. Dr. Gilani’s efforts have earned praise, notably from the President of Pakistan Mr. Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghari, who commended his relentless advocacy for the self-determination of the Kashmiri people. His work embodies a steadfast commitment to justice and humanitarian causes, earning him recognition as a distinguished OP-ED writer and a champion of human rights on the global stage. He has remained a strong supporter of a dialogue between India and Pakistan and continues to urge them to respect the UN template on Kashmir. In October 1996, Major General Alfanso Passolano, the Chief of UNMOGIP, received special clearance from the UN headquarters in New York to fly from Srinagar to Rawalpindi. He held a meeting with a 5-member delegation from JKCHR, headed by Dr. Gilani. This historic meeting lasted for over three hours, and delved deep into the complex dynamics of the Kashmir conflict. It was the first instance of such high-level engagement between UNMOGIP and representatives from either side of the ceasefire line in Kashmir. Dr. Gilani’s has campaigned for the independence of judges and lawyers in Pakistan and Azad Kashmir during the lawyer’s movement in Pakistan. He has represented Benazir Bhutto, Asif Ali Zardari, Nawaz Shari, Shahbaz Sharif, Yousuf Raza Gilani and many other politicians at the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva. Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani has been a member of the International Platform of Jurists for East Timor since 1984, making significant contributions to East Timor’s independence. He is also a dedicated advocate for the Palestinian cause and has actively defended the human rights of minorities in Iraq and Kashmir at the United Nations. Currently, Dr. Gilani serves as the President of the Jammu and Kashmir Council for Human Rights (JKCHR), a non-governmental organization with special consultative status at the United Nations. The UN Secretary-General has received over 60 papers from JKCHR, which have been released as UN General Assembly documents on Kashmir during the UN Human Rights Council sessions in Geneva. The NGO contends for the UN supervised vote on the future of Kashmir. His dedicated work on the four components of Rights Movement, namely, rights, dignity, security and self-determination of all the people of Jammu and Kashmir, remains a lead and a reliable reference. The Co-Chairman PPP Asif Ali Zardari nominated Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani on 12 April 2008 as the first person in the list of 12 other people to receive the “Tipperary International Peace Award” conferred posthumously on Shaheed Mohtarama Benazir Bhutto in a ceremony in Tipperary, Ireland on Friday April 25, 2008. He has remained closely associated with three Bhutto’s – Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Nusrat Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto. Martial Law Government of General Zia ul Haq, booked him under Martial Law Regulations 13 and 53 for his advocacy of Kashmiri language and other published work. MLR 13 prescribed 5 years imprisonment and whipping up to 15 lashes and MLR 53 prescribed a death sentence. On 3 September 1982 Amnesty International cautioned Government of Pakistan that, “Should he be arrested on this charge, he would certainly be eligible for adoption as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.” Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

Welcome to my Blog

You may be following me on Facebook, WhatsApp and X. I appreciate your kind and valuable interest. This blog is dedicated to elucidating the various variables of Kashmir Case. Here, we will explore the jurisprudence of Kashmir case. Kashmiris are not a subordinate people; their title is based on the principle of equality. Constituency of Reliable Information There is an urgent need to enlarge the constituency of reliable information and knowledge about Kashmir case. It will include interpretation of the title of the people to self-determination, explaining the United Nations’ template and the interpretations of the respective Indian and Pakistani claims. The Indian and Pakistani claims are a consequence of the Kashmiri people’s title to self-determination. June 2018 and July 2019 UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Reports have asked India and Pakistan to “Fully respect the right of self-determination of the people of Kashmir as protected under International Law. You have to be vigilant. Government of Pakistan has failed to spot that these two UN Reports have referred to Indian Administered Kashmir no less than 17 times as “Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir”. Unfortunately, not a single person from the Government of Azad Kashmir, its administration, judiciary, civil society, or general citizenry has raised concerns with the Government of Pakistan regarding this terminology. It has appeared 9 times in the 2018 report and 8 times in the 2019 report. We need a modern-day Diogenes with his lantern to keep a sharp vigil. Independent and Sovereign StateThe political arrangement of Jammu and Kashmir with the British Crown came to an end on 15 August 1947. Maharaja of Kashmir was under the Paramountcy of the British Crown before the partition of India from 15.8.1947 under section 7, Indian Independence Act. The Suzerainty of the Crown over Jammu and Kashmir lapsed and all functions exercisable by His Majesty at that date with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir, all obligations of His Majesty towards the Jammu and Kashmir State or the ruler thereof and all powers, rights, authority or jurisdiction exercisable by the Crown at that date in relation to the State of Jammu and Kashmir by treaty or otherwise lapsed and the State became an independent and sovereign State in the full sense of the International Law. “Thus whatever limits to the sovereignty of His Highness in relation to matters coming within the sphere of paramountcy existed before 15.8.1947, these ceased to exist and His Highness became an uncontrolled and absolute sovereign even in relation to such spheres from that.” (Janki Nath Wazir CJ and Shahmiri J in Magher Singh v Principal Secretary J & K Government 1953). Jammu and Kashmir State, by virtue of an Instrument of Accession made on 26 October 1947 ceded a limited authority specified in Section 6 (1) (a) in regards to Defence, External Affairs and Communication to the Dominion of India. Clause 8 of the Instrument of Accession runs as follows: “Nothing in this Instrument affects the continuance of my sovereignty in and over this State, or save as provided by or under this Instrument the exercise of any powers, authority and rights now enjoyed by me as Ruler of this State or the validity of any law at present in force in this State.” It is a clear and express reservation. No change whatsoever was affected in the residuary sovereignty of the State or the power of its Ruler so far as the succession of the State to the Dominion of India is concerned. The residuary sovereignty of the State and the powers of its ruler in matters other than those specified in the Instrument of Accession remained unaffected. Promise made to the Government of KashmirOn 27 October 1947, the Governor-General of India, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, informed the Maharaja of Kashmir: “In response to your Highness’ appeal for military aid, action has been taken today to send troops of the Indian Army to Kashmir to help your own forces to defend your territory and protect the lives, property, and honour of your people.” The Governor-General made it clear that this military support was conditional. He stated: “In accordance with the policy that in the case of any State where the issue of accession has been the subject of dispute, the question of accession should be decided in accordance with the wishes of the people of the State, it is my Government’s wish that as soon as law and order have been restored in Kashmir and her soil cleared of the invader, the question of the State’s accession should be settled by a reference to the people.” Indian army remains as a sub-ordinate force under the State administration and a supplement to Maharaja’s forces. The ultimate decision regarding Kashmir’s accession was to be made through a democratic process, reflecting the will of the Kashmiri people. Promise made to the Government of PakistanIn a telegram dated 27 October 1947, the Prime Minister of India assured the Prime Minister of Pakistan with the following statement: “I should like to make it clear that the question of aiding Kashmir in this emergency is not designed in any way to influence the State to accede to India.” This assurance, conveyed from one Prime Minister to another, is a significant state document. Given the developments of that time, Pakistan was understandably concerned. The Prime Minister of India provided further reassurance with these words: “I should like to make it clear that the question of aiding Kashmir in this emergency”—referring to efforts to eliminate tribal incursions and quell the rebellion—”is not designed in any way to influence the State to accede to India. Our view, which we have repeatedly made public, is that the question of accession in any disputed territory or State must be decided in accordance with the wishes of the people, and we adhere to this view.” In a subsequent telegram dated 31 October 1947, the Prime Minister of India reiterated to the Prime Minister of Pakistan: “Our assurance that we shall withdraw

Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto, exchanging written notes with Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani at an intra-Kashmir conference in London

Yasser Arafat Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization receiving Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani at a special one on one meeting in London