A careful and unbiased examination of the role of the politicians of Azad Kashmir after the re-constitution of the Government of Azad Kashmir on 24 October 1947 and the assurance of the Government of Pakistan held out to the UNCIP delegation in September 1948, we see that both Governments have reneged on their first declared positions. Neither the Government of Azad Kashmir carried on the terms of the Provisional Declaration nor did the Government of Pakistan honour her assurance to let the Government of Azad Kashmir to speak directly to UN or through it as its medium. United Nations had fully explained and expressed a full regard to safeguard law and order, the integrity of the cease-fire-line and the security of the territory on each side of that line. It was on this basis that UNMOGIP were brought in, in January 1949. Clause A.3 of Part II of the UNCIP resolution of 13 August 1948 provided that pending a final solution, the territory evacuated by Pakistan troops will be administered by the local authorities under the surveillance of the Commission. In its letter dated 3 September 1948, the Commission defined the “evacuated territory” to mean “those territories in the State of Jammu and Kashmir which are at present under the effective control of the Pakistan High Command”. (UNCIP’s First Report, Paragraph 90). As a result of the demarcation of the cease-fire line all territories situated on the Pakistan side of the cease-fire line should be regarded as “evacuated territory”. The United Nations Commission told the Foreign Minister of Pakistan that by the term “local authorities” it meant the Azad Kashmir Government, though the Commission could not accord de jure recognition to a revolutionary authority such as the Azad Kashmir Government. The Commission also gave the assurance that no official of the Government of India, or of the Maharaja’s Government, would be permitted to enter the evacuated territory. (Vide UNCIP’s Summary-Record of the meeting held on 31 August 1948). Azad Kashmir Government was recognised a de facto revolutionary authority. However, the de jure sovereign authority was accorded to Government of Jammu and Kashmir, duly established by the Maharajah of Kashmir and re-organised under the supervision of Sheikh Abdullah. The Government of India maintained, “that the administration of “this area would, under para 3 of Part II of the Resolution of 13 August 1948, vest in local authorities to be established or recognized for the purpose; to these local authorities under the same resolution only local administrative functions have been assigned. In the very nature of things such authorities can be in charge only of local law and order whether in the area or with reference to the cease-fire line. To give them any armed force equivalent to troops would not be consistent either with their status or with their functions and would be a violation of the sovereignty of the Union of India and the Jammu and Kashmir state. In the very nature of things, therefore, these local authorities can be entrusted only with a civil armed force.” In regards to settle an unease and a growing feeling of an inequity in the balance of the two forces in character and number, on either side of the cease-fire-line United Kingdom made an important observation at the 606 th meeting of the UN Security Council ……It stated that, “United Kingdom Government has never thought that the proposal to limit the forces on the Pakistan side of the cease-fire line to an armed civil police force while leaving a military force on the other side of the cease-fire line was consistent with a really free plebiscite”. The Government of India made an accommodating response and said that, she considered “a civil armed force of 4,000 would be on the liberal side considering the pre-aggression strength of forces policing this area. However, they would be prepared to consider an appropriate increase to provide for the needs of the Northern areas or should the United Nations Representative, under whose surveillance these forces would be operating, make out a case that this strength is inadequate”. The remaining Azad Kashmir forces had to be “separated from the administrative and operational control of the Pakistan High Command and will be officered by neutral and local officers under the surveillance of the UnitedNations”. UNCIP had fully succeeded in reconciling India and Pakistan that “Pending a final solution the territory evacuated by the Pakistan troops will be administered by the local authorities under the surveillance of the United Nations. The local authorities shall undertake the fulfilment of such duties as are necessary for the observance within that territory of the provisions of the Karachi Agreement of 27 July 1949”. We find that diplomacy in Islamabad, got hooked on, other interests sans Kashmir. It addressed itself and full time, to the three issues, namely, (i) division of military stores, (ii) division of cash balances and on the (iii) interference with the reserve Bank so as to destroy the monetary and currency fabric of Pakistan. The politicians in Azad Kashmir, fell on the bones of greed and started looking for patronage in Pakistan. It needed a climb down and restricting a culture of corruption and quid pro quo. Leadership in Azad Kashmir did not have the capacity or if it had any, it was very inadequate to keep on prosecuting the principle of ‘equality’ and ‘self-determination’ and seek to correct any harm caused by any wrong interpretation of their case. It off loaded itself from the train and failed to work out the benefits of a “Local Authority” under the surveillance of United Nations. It failed to hold on to its de facto recognition as a “revolutionary authority”. We find that Government of Azad Kashmir did not ask for any representation at the Geneva Conference held from 26 August to 10 September 1952, on the “implementation of UNCIP Resolutions”. Jammu and Kashmir on the Indian side of cease fire line was represented by a Kashmiri Pandit, Mr. D.P. Dhar, Deputy Minister,

The giant ‘Broken Chair’

Pakistan’s Kashmir Policy – IIIMake a joint war on them Pending a UN supervised vote in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, the Government of Indiahas taken upon to “help Kashmir forces to defend the territory and to protect the lives, property and honour of the people”. This commitment stands in regards to the State as a whole and to all people of the State. UN discipline has set out three more restraints on the appearance, number and location of Indian army. Pakistan formally became a party to the discussion on the “Situation in Jammu and Kashmir” at the UN Security Council on 15 January 1948. It has flagged its role, to provide political, moral and diplomatic support to the people of the State. In addition it has ‘assumed’ specified responsibilities in Azad Kashmir under UNCIP Resolutions. Pakistan has entered into a detailed Agreement, called, Karachi Agreement with the Government of Azad Kashmir and the only political party which was functional in April 1949. In her reference made under Article 35 of the UN Charter the Government of India had pleaded that, “Invaders are still on the soil of Jammu and Kashmir and the inhabitants of the State are exposed to all the atrocities of which a barbarous foe is capable …The matter is therefore one of extreme urgency and calls for immediate action by the Security Council for avoiding a breach of international law”. Government of India made three immediate demands. In her reference she has stated that, “The Government of India deeply regret that a serious crisis should have been reached intheir relations with Pakistan. Not only is Pakistan a neighbour but, in spite of the recent separation, India and Pakistan have many ties and many common interests. India desires nothing more earnestly than to live with her neighbour-state on terms of close and lasting friendship. Peace is to the interests of both States; indeed to the interests of the world”. In its submissions in Document II titled “Pakistan’s Complaint Against India” Government of Pakistan submitted that “The tragic events and the happenings in East Punjab and the Sikh and Hindu States in and around that Province had convinced the Muslim population of Kashmir and Jammu State that the accession of the State to the Indian Union would be tantamount to the signing of their death warrant”. Pakistan does not deny the outside incursion into the State. In her Document III titled “Particulars of Pakistan’s Case” Pakistan submits that, “In conspiracy with the Indian Government, they seized upon this incursion as the occasion for putting into effect the pre-planned scheme for the accession of Kashmir as a coup d’état and for the occupation of Kashmir by the Indian troops simultaneously with the acceptance of the accession by India”. The submission adds that, “The Pakistan Government have not accepted and cannot accept the accession of Jammu and Kashmir State to India. In their view the accession is based on violence and fraud. It was fraudulent in as much as it was achieved by deliberately creating a set of circumstances with the object of finding an excuse to stage the “accession”. It was based on violence because it furthered the plan of the Kashmir Government to liquidate the Muslim population of the State”. The sequence of events described in the Pakistan Document III do not fully agree with the Rights Movement of the people of Jammu and Kashmir. People had raised the issue of misgovernment and mal-administration in 1877. In 1888, the British Government asked the Maharaja to make certain reforms in the administration. Under a false pretext of conspiring with the Czar of Russia Maharaja was deposed for a while and when restored in authority in 1905, he was made subject to the veto of the Resident. Maharaja kept on working with limited powers till 1921. The first major demand was “State for the State’s People”. Kashmiris, who had hitherto been excluded from the affairs of the State, strongly resented the encroachment from outside. As education advanced, this resentment, which had been growing for the past half-century became stronger. The slogan “State for the State’s People” came to be heard everywhere. One can trace the desire for social justice as far back as to 1877. It was in October 1924, that the people of Kashmir presented a 17-demands memorandum to Viceroy Lord Reading. The major demand was that the “Muslim representation in the State Council should be according to their ratio in the population”. Therefore, the submission of a likening of Kashmir situation to what happened in East Punjab, in Sikh and Hindu States, does not hold strong. By 1932, people of Kashmir, had moved to third important demand for a “responsible government”. There is another puzzle in the submissions made by the Government of Pakistan in her Document III. All the love and affection shown for the honour and the welfare of the people of Kashmir, in particular, the Muslims has evaporated in thin air. While making an argument in reference to “the forces of the Azad Kashmir Government”, Pakistan has referred to an earlier proposal that it had made in November 1947 to the Government of India. It was to make a “joint war on them”, that is, on the independent tribesmen and the forces of the Azad Kashmir Government. The offer to wage a joint war, would occupy the interest of the present and future generations. Historians would have a subject of prime interest. The proposal does not remain in line with the fundamentals of the case presented by the Government of Pakistan at the UN Security Council. Nor has it ever before surfaced for a thorough debate. Dr Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

Calendar

Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani

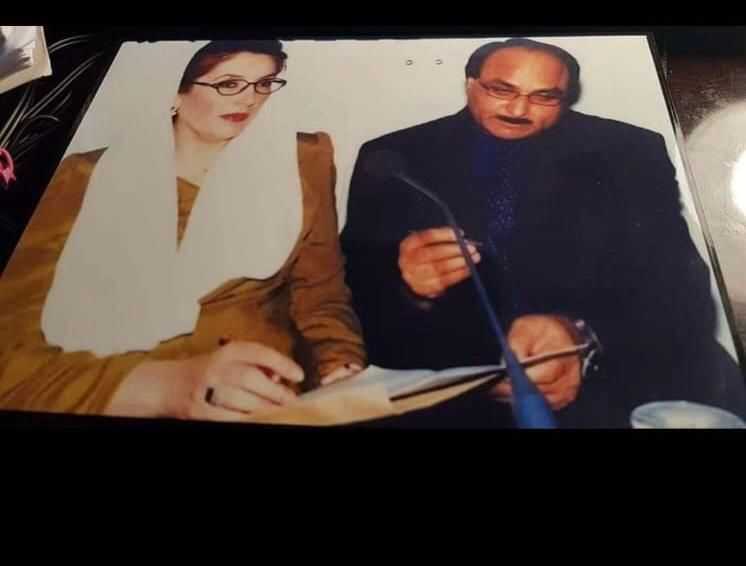

Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani hails from the historic village of Naranthal, also known as Jalsharee. The village sits on the banks of the river Jhelum. It is a modest geographical tributary of District Baramulla, Kashmir. Renowned for its Naranthal Temple and the refreshing Jalshree spring, the village shares its boundaries with two other villages Khadaniar (Khadniyar) and Drangbal, also known as Takisultan. The lineage of the Gilani family traces back to Baghdad, Iraq, journeying through Peshawar in British India and Lahore before settling in Khanyar, Srinagar, Kashmir, where they serve as Gaddi Nashin’s of the shrines of Dastgeer Sahib. Dr. Gilani’s educational journey traversed through the corridors of Government Middle School Khadniyar, Government Higher Secondary School Baramulla, and Degree College Baramulla. He pursued English Literature & Politics at the University of Kashmir, Law at S M Law College Karachi, Islamic Law at Kings College London, and International Law at Queen Mary University London. Additionally, his academic pursuits extended to Victimology at IUC Dubrovnik, in former Yugoslavia, and Peacekeeping/Humanitarian Operations & Election Monitoring in Pisa, Italy, under the 1996 UN and European Commission Programme. He stands as one of the select 40 individuals chosen under this esteemed program and holds a Ph.D. in the Jurisprudence of UN Resolutions and the Kashmir Case. His notable engagements include representing Unrepresented Peoples and Nations on the 33-member UN-NGO-Liaison Committee at the UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna (1993), where he also served on the UN-NGO Liaison Diplomatic Committee. Dr. Gilani addressed the Plenary and the Main Committee of the Conference, leaving an indelible mark with his insights. Begum Nusrat Bhutto from Pakistan and Atal Bihari Vajpayee from India, also addressed the Plenary and the Main Committee of the Conference on behalf of their respective countries. Dr. Gilani authored a chapter on Juvenile Justice in Saudi Arabia for a seminal work titled “Delinquency and Juvenile Justice in the Non-Western World,” providing invaluable insights for students, scholars, and practitioners. Acknowledged by the United Nations since January 1990, Dr. Gilani has lent his expertise to various international platforms, including the UN Commission for Human Rights, UN Sub Commission for Human Rights, UN Human Rights Council, Islamic Summit in Casablanca, and CHOGM-93. His commitment to promoting and safeguarding human rights transcends borders, evidenced by his diverse professional engagements, including roles at the Ministry of Information Government of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan Red Cross, Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation, and the UNHCR/UKIAS Refugee Section in London. He became the first Muslim Director of Millan Asian Centre in London and was elected on the General Council of UKIAS. Dr. Gilani’s efforts have earned praise, notably from the President of Pakistan Mr. Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghari, who commended his relentless advocacy for the self-determination of the Kashmiri people. His work embodies a steadfast commitment to justice and humanitarian causes, earning him recognition as a distinguished OP-ED writer and a champion of human rights on the global stage. He has remained a strong supporter of a dialogue between India and Pakistan and continues to urge them to respect the UN template on Kashmir. In October 1996, Major General Alfanso Passolano, the Chief of UNMOGIP, received special clearance from the UN headquarters in New York to fly from Srinagar to Rawalpindi. He held a meeting with a 5-member delegation from JKCHR, headed by Dr. Gilani. This historic meeting lasted for over three hours, and delved deep into the complex dynamics of the Kashmir conflict. It was the first instance of such high-level engagement between UNMOGIP and representatives from either side of the ceasefire line in Kashmir. Dr. Gilani’s has campaigned for the independence of judges and lawyers in Pakistan and Azad Kashmir during the lawyer’s movement in Pakistan. He has represented Benazir Bhutto, Asif Ali Zardari, Nawaz Shari, Shahbaz Sharif, Yousuf Raza Gilani and many other politicians at the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva. Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani has been a member of the International Platform of Jurists for East Timor since 1984, making significant contributions to East Timor’s independence. He is also a dedicated advocate for the Palestinian cause and has actively defended the human rights of minorities in Iraq and Kashmir at the United Nations. Currently, Dr. Gilani serves as the President of the Jammu and Kashmir Council for Human Rights (JKCHR), a non-governmental organization with special consultative status at the United Nations. The UN Secretary-General has received over 60 papers from JKCHR, which have been released as UN General Assembly documents on Kashmir during the UN Human Rights Council sessions in Geneva. The NGO contends for the UN supervised vote on the future of Kashmir. His dedicated work on the four components of Rights Movement, namely, rights, dignity, security and self-determination of all the people of Jammu and Kashmir, remains a lead and a reliable reference. The Co-Chairman PPP Asif Ali Zardari nominated Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani on 12 April 2008 as the first person in the list of 12 other people to receive the “Tipperary International Peace Award” conferred posthumously on Shaheed Mohtarama Benazir Bhutto in a ceremony in Tipperary, Ireland on Friday April 25, 2008. He has remained closely associated with three Bhutto’s – Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Nusrat Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto. Martial Law Government of General Zia ul Haq, booked him under Martial Law Regulations 13 and 53 for his advocacy of Kashmiri language and other published work. MLR 13 prescribed 5 years imprisonment and whipping up to 15 lashes and MLR 53 prescribed a death sentence. On 3 September 1982 Amnesty International cautioned Government of Pakistan that, “Should he be arrested on this charge, he would certainly be eligible for adoption as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.” Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto, exchanging written notes with Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani at an intra-Kashmir conference in London

Yasser Arafat Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization receiving Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani at a special one on one meeting in London