Calendar

The Azad Kashmir Government was recognized to hold direct discussions with the Commission

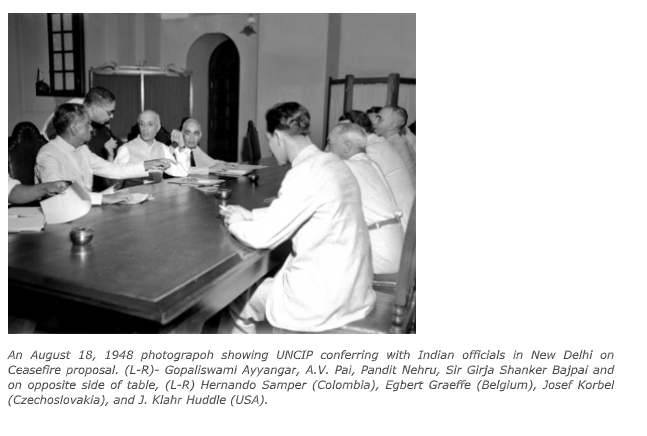

A Government was reconstituted on October 24, 1947. It was intended to be a non-communalgovernment, comprising both Muslims and non-Muslims in the cabinet. This provisionalgovernment was to be temporary, tasked with restoring law and order in the State, enablingthe people to elect a popular legislature and government through free elections. The newly constituted Provisional Government expressed sentiments of utmost “friendlinessand goodwill towards its neighbouring Dominions of India and Pakistan,” hoping that “boththe Dominions of India and Pakistan will sympathize with the people of Jammu and Kashmirin their efforts to exercise their birth right of political freedom.” It assured that it would“safeguard the identity of Jammu and Kashmir as a political entity.” The personality of the “Azad Kashmir Government” was acknowledged by the UNCIP(United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan), which received its communication onJuly 8, 1948. UNCIP delegations visited Azad Kashmir on September 4 and September 14,1948. Sir Mohammad Zafrullah Khan, Foreign Minister of Pakistan cited three reasons motivatingthe entry of Pakistani troops into Kashmir: At its 19th meeting on July 20, 1948, UNCIP prepared a confidential cable informing theSecurity Council of the presence of Pakistani troops in Kashmir. The UNCIP delegationreported that “As for the views of the Azad Kashmir people, the Foreign Minister’s intentionwas not to induce the Commission into recognizing the ‘Azad Kashmir Government,’ but hefelt that their approval, whether expressed directly to the Commission by their representativesor through the medium of the Pakistan Government, might be of decisive importance.” It was clear that the “Azad Kashmir Government” was free to represent its people throughtheir representatives at the UN and additionally had the option to use the medium of thePakistan Government. On September 6, 1948, at the 55th meeting, the Commission receiveda letter from the Government of Pakistan addressing various issues related to the UNCIPResolution of August 13, 1948. The letter clarified, “They (Pakistan) desire to make it clear atthe outset that these views are the views of the Government of Pakistan and are not in anysense binding upon the Azad Kashmir Government, nor do they reflect the views of the AzadKashmir Government.” UNCIP also made it clear that it intended to hold discussions with theAzad Kashmir representatives as individuals. The letter further stated, “The Government of Pakistan would at all times be prepared to useits good offices to persuade the Azad Kashmir Government to accept the views of theproposals of the Commission which the Pakistan Government themselves take, but suchacceptance must rest finally with the Azad Kashmir Government themselves.” The Government of Pakistan highlighted an important distinguishing factor regarding AzadKashmir. The letter addressed to the Commission stated, “As has already been explained to the Commission, political control over the Azad Kashmir Forces vests in the Azad KashmirGovernment, and it is the latter Government alone that has the authority to issue a cease-fireorder to those forces and to conclude terms and conditions of a truce that would be bindingupon these forces.” Thus, the Azad Kashmir Government was recognized to hold direct discussions with theCommission and was acknowledged to have the authority to order a cease-fire. Dr Syed Nazir Gilani. Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com.

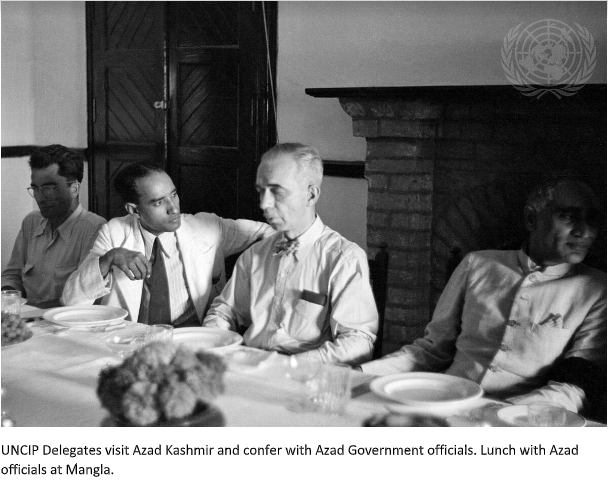

UNCIP Visits to Azad Kashmir

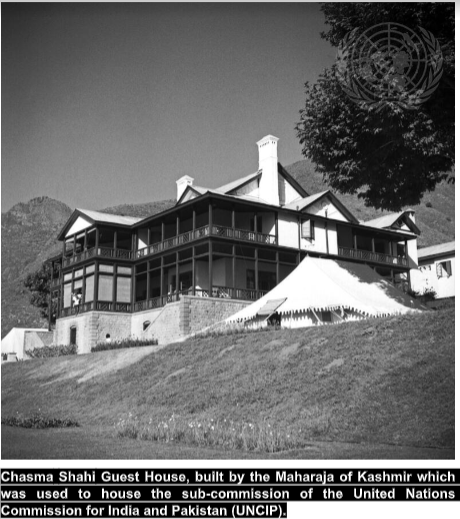

On July 8, 1948, the President of the Azad Kashmir Government, Sardar Mohammad IbrahimKhan, lodged a formal protest with the Chairman of the United Nations Commission for Indiaand Pakistan (UNCIP). He highlighted that the Azad Kashmir Government was not given anopportunity to present its perspective during the UN debates on Jammu and Kashmir fromJanuary to April 1948. The protest letter emphasized that “the failure of the Security Council to grant a hearing tothe Representative of the Azad Kashmir Government was a serious injustice to the people ofJammu and Kashmir.” It urged the UNCIP to visit Azad Kashmir at the earliest opportunity. The UNCIP Chairman accepted the invitation from the Azad Kashmir Government, and theCommission visited Azad Kashmir in September 1948. On September 4, the Commission metinformally with representatives of the Azad Movement, including Chaudri Ghulam Abbas,Supreme Head, and Sardar Mohammad Ibrahim Khan, President. Mr. Abbas argued that Part III of the Resolution should have been the first step, although hedid not object to Parts I and II. He believed that once the conditions for a plebiscite wereagreed upon, implementing a cease-fire agreement would be straightforward. Sardar Ibrahimemphasized that the Resolution did not ensure India’s complete acceptance of the specificconditions for a plebiscite, the fairness and impartiality of which could be determined by theCommission. He stated that an unconditional cease-fire was unacceptable. Following this, the Commission formed an investigating sub-committee. On September 14,1948, this group, led by Mr. Huddle (United States) and including Mr. E. Graeffe and Mr. H.Graeffe (Belgium), Major Smith (United States), and two members of the Secretariat, visitedvarious localities in Azad Kashmir. They held discussions with key figures of the AzadGovernment. The group returned to Srinagar on September 18 and provided a detailed reportto the Commission. On September 19, the Commission convened its 62nd meeting in Srinagar, where it approvedthe text of a reply to a letter from Sir Zafrullah Khan dated September 6. The Government of India submitted to the Commission that “The evacuated territoriessituated outside the fixed line should be provisionally administered by existing localauthorities, or, if necessary, by local authorities designated by the Commission. They shouldbe supervised by observers of the Commission but remain under the sovereignty of the stateof Jammu and Kashmir until the final settlement of the dispute between India and Pakistan.” In September 1948, the Government of Azad Kashmir established a working relationshipwith the UNCIP, marking a significant diplomatic milestone in its international relations.

Azad Kashmir Government’s invitation to UNCIP and Memorandum

Azad Kashmir Government formally reconstituted itself on 24 October 1947. “TheProvisional” declaration admits that it is a consequence of the “The Provisional AzadGovernment, which the people of Jammu and Kashmir have set up few weeks ago with theobject of ending intolerable Dogra tyrannies and securing to the people of the State, includingMuslims, Hindus and Sikhs, the right of free self-Government has now established its ruleover a major portion of the State territory and hopes to liberate the remaining pockets ofDogra rule very soon.” The announcement of 4 October 1947 establishing Azad KashmirGovernment is acknowledged and carried forward. After this re-constitution, Azad Kashmir Government expressed itself for the first time as a“free self-Government” and its President addressed a letter dated 8 July 1948 to the Chairmanof the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan. It expressed its regrets that theSecurity Council gave India, Pakistan and Head of the Emergency Administration SheikMohammed Abdullah a “very full hearing” and allowing no opportunity to the Representativeof Azad Kashmir Government, to place its point of view before the United Nations”. Azad Kashmir Government invited members of the UNCIP to visit Azad Kashmir at theearliest, “to see with your own eyes the havoc wrought by the Indian Army and the heroicstruggle of our people, and to discuss with our representative ways and means to bring to aspeedy end this tragic state of affairs”. Azad Kashmir Government set out 8 conditions, in order to be able to agree to “participate inthe plebiscite and be bound by its results”. In para 11 the letter stated “We will be glad to discuss with the Commission the conditions onwhich the Azad Kashmir Government could agree to participate in the plebiscite and bebound by its results. Some of these have already been mentioned in the statements made fromtime to time by the Quaid-i-Millat Chowdhury Ghulam Abbas, myself and my colleagues.Others would have to be worked out in the light of the conditions now obtaining and futuredevelopments. The principal conditions are, however, enumerated below”: a. The Indian Armed forces, and the Sikh and R.S.S assassins must be completely withdrawn.b. Military and police forces required for internal security and the maintenance of lawand order should be raised locally, and be under the control of the PlebisciteAdministrator until the plebiscite is over.c. A Provisional Government should be set up which should reflect the will of themajority of the people. As the Muslim Conference enjoys the confidence of the vastmajority of Muslims of Jammu and Kashmir, who constitute nearly 78% of the State’spopulation, it should assume the main responsibility for forming the ProvisionalGovernment, and should provide the Prime Minister. We would welcome the co-operation of other political parties, but I would like to make it perfectly clear that,under no circumstances, would the representatives of the Muslim Conference and theAzad Kashmir Government agree to the continuance as Prime Minister of SheikhAbdullah, who has been playing the role of a Quisling and is a traitor to his owncountry. d. If a popular Government cannot be immediately established, we would agree to thesetting up of a completely neutral administration under the supervision and control ofthe United Nations’ Commission until the plebiscite is over.e. All political prisoners must be released and all political parties granted the fullestfreedom to propagate their views and ideas.f. All State employees who have been dismissed since 15 August 1947 because of theiralleged sympathies for Pakistan should be re-instated.g. The Commission should ensure the restoration and rehabilitation of all residents ofJammu and Kashmir who have left, or who have been compelled to leave the Statesince August 1947.h. The Plebiscite Administrator should have under its full and effective control, not onlythe armed forces and the police stationed within the country, but also theadministrative and judicial machinery, and should thus be in a position to ensure afree and impartial plebiscite.i. The future constitution of the State should be decided by its own people, inaccordance with recognised democratic methods. “The Azad Kashmir Government feel that these are the minimum conditions which mustbe satisfied before they could commit themselves and their people to the solutionproposed by the Security Council.”UNCIP accepted the invitation from Azad Kashmir Government and visited Azad Kashmiron 4 September 1948. Dr Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

Jurisprudence of Bilateralism

Relations between India and Pakistan continue to be bedevilled for the last 77 years (1947-2024). It is because the ‘nationalists of opportunism’ in politics far exceed the ‘nationalists of conviction’. India and Pakistan are contributing to peace-making around the world. Unfortunately, both have failed to roller skate good neighbourly relations and own the scope of bilateralism at home, to settle disputes and promote peace and welfare of their people. It was the failure in bilateral engagement under article 33, that Indian Government has invoked article 34 at the UN Security Council. Investigated dispute Kashmir dispute has been duly debated at the UN Security Council, fully investigated under the authority of UN Security Council and a UN mechanism to hold a referendum under the supervision of the United Nations awaits compliance by India and Pakistan. Article 33 of the United Nations promotes bilateral engagement between parties and Kashmir is no exception. The importance of bilateral engagement between India and Pakistan has been duly entertained during the debates on Kashmir at the UN Security Council. The door of bilateralism should be kept wide ajar, for a conclusive success of the regime of bilateralism, and at the same time they shall have to remain consistent with the principles of UN Charter. Scope of bilateralism The scope of bilateralism on Kashmir has been explained and settled by United States of American at the 607th meeting of the UN Security Council held on 5 December 1952. Ernest A Gross US Representative at the Security Council at the 607th meeting of UN Security Council on 05 December 1952 has made a case for bilateral dialogue as follows: “It seems to me that the principles on which we are trying to proceed to assist the parties to carry out their Charter obligations are these: In the first place: As member nations of United Nations India and Pakistan, have Charter obligations to settle disputes peacefully between themselves and to co-operate in promoting peace in other parts of the world. Intra-State obligations conjoin with Charter obligations, and make a stronger case for Bilateralism. India and Pakistan have, caused in addition to Charter obligations and intra-state obligations, a substantive and a rich jurisprudence of Bilateralism. The problem remains that it has been only rendered on paper and the two counties have failed to put that into practice. The importance of bilateral engagement between India and Pakistan has been duly entertained during the debates on Kashmir at the UN Security Council. Tashkent Declaration Tashkent Declaration of 1966, Shimla Agreement of 1972, Lahore Declaration of 1999, establish a formal regime of principles, in the conduct of bilateral relations and the settlement of disputes. Shimla Agreement Shimla Agreement under clause (ii) causes a jurisprudence of ‘Peaceful Means’. The two countries are resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations or by any other peaceful means mutually agreed upon between them. In Shimla it has been agreed, that ‘both shall prevent the organisation, assistance or encouragement of any acts detrimental to the maintenance of peaceful and harmonious relations’. Lahore Declaration It is important to note that Tashkent Declaration and the Shimla Agreement commit their jurisprudence to UN Charter obligations and to the final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir dispute. The Lahore Declaration of February 1999, on the one hand reiterates a ‘determination to implement the Shimla Agreement in letter and spirit’ and on the other introduces the ‘sanctity’ clause in respect of line of control, a singular addition to the existing bilateral jurisprudence on Kashmir. Skipped a reference to the UN Charter Additionally, at Lahore, the parties for the first time skipped a reference to the UN Charter and to a no prejudice clause that existed in Tashkent Declaration and Shimla Agreement. This does not prejudice the prevailing authority of article 103 of the UN Charter.India – Pakistan Relations, need to be roller-skated on the principles and scope of Bilateralism. The conduct of the wisdom of this bilateralism in reference to UN Charter and a no prejudice clause makes it fair to the two sovereign states and the People of Jammu and Kashmir. Principal interests on balance Although the principal subject of dispute – the people of Jammu and Kashmir, were not represented or adequately represented at any of these fora i.e.; the UN, at Tashkent, at Shimla and at Lahore, yet, prima facie, their principal interests on balance have not suffered any prejudice. Indian interpretation of bilateralism has no merit as article 103 of UN Charter shall always prevail. Article 103 of UN Charter says that in case of treaties between countries which are incompatible with the Charter, obligations derived from the Charter must prevail. As member nations of United Nations India and Pakistan, have Charter obligations to settle disputes peacefully between themselves and to co-operate in promoting peace in other parts of the world. A collective commonality India-Pakistan Relations and The Scope for Bilateralism hinges on the shortlisting of the grievances of the people of Jammu and Kashmir. The poise of grievances, in the beginning, has to be separate and the same could be developed into a collective commonality. India and Pakistan, in view of the broad and rich spread of 77-year-old jurisprudence (1947-2024) of bilateralism, committed in reference to UN Charter, shall have to focus on all political disputes that threaten peace. India and Pakistan shall have to improve relations and begin talking sooner rather later. The regime of bilateralism between India and Pakistan would work, if they flag the fact that the people of Jammu and Kashmir are neither an adjunct nor an adjective – but a ‘principal essential’, on their own and in the India-Pakistan relations. The door of bilateralism should be kept wide ajar, for a conclusive success of the regime of bilateralism, and at the same time they shall have to remain consistent with the principles of UN Charter. Dr Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

Kashmiri Waters and self-determination

UN General Assembly in July 2010 recognized that access to water and sanitation as a fundamental right but did not specify that the right entailed legally binding obligations. Governments of Germany and Spain, with support from many others tabled a resolution to close the legal gap by clarifying the foundation for recognition of the rights and the legal standards which apply. The UN Human Rights Council has affirmed that the right to water and sanitation is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living. India and Pakistan are locked in a continuous clash of claims over water in Jammu and Kashmir. Water resources are not unlimited and available forever. The actual stewardship of water resources in any part of Kashmir rests with the people of Kashmir. Water politics between India and Pakistan is strange and very interesting. It exposes the manner in which the two countries have been shifting the goal posts of their interests. They have failed to appreciate that water in Kashmir is a natural resource and is embedded in the natural habitat of the disputed State. It is a trust property and remains part of the self-determination package on Kashmir. It is a violation of trust that India and Pakistan have been taking unilateral decisions in regard to water in Kashmir. Both countries have failed to incorporate the right of the people of Kashmir in the management of water uses and water-related activities under the Indus Water Treaty. Governments must fully implement their obligations to create an enabling environment and to regulate and monitor the right to water and sanitation in the three administrations of Kashmir. On 21 August 1957 Indian Government reported to UN Security Council that Pakistan was likely to execute Mangla Dam Project in Mir Pur and exploit the “resources of the territory to the disadvantage of the people of Jammu and Kashmir and for the benefit of the people of Pakistan”. The Indian letter S/3869 dated 22 August 1957 flagged that the action of the Government of Pakistan was a violation of the Security Council Resolution of 17 January 1948. The complaint further reiterated that the Government of the State of Jammu and Kashmir is the only lawful Government of the State under the Resolutions of 13 August 1948 and 5 January 1949. India also filed a three page report titled “The Mangla Dam Project” marked at the UN Security Council as S/3869. It is only a few years down the road that in 1960 India and Pakistan entered into Indus Water Treaty to share the Waters of Kashmir. The extent to which Pakistan failed to appreciateits obligations towards water as a trust property, is revealed by the broadcast of Ayub Khan to the nation made on 4 September 1960. He said that the terms of the Treaty were “the best we could get under the circumstances, many of which, irrespective of merits and legality of the case, are against us”. There is a sense of apology and it implies that something had been sacrificed by Ayub Khan in the process. Keeping out the full regime of politics of Kashmir dispute, waters are the natural resource embedded in the disputed habitat of Kashmir. India and Pakistan could not have these waters with ‘no holds barred’. Waters and other natural resources have to be recognised as trust properties by India and Pakistan. People have to defend these natural resources of Kashmir. The use of water in the Indus Water Treaty has not been aligned on a principled, fair and just basis. It does not recognise the interests of the affected people (Kashmiri) and has failed to develop a mechanism to include those interests in water allocation decision. Under the Treaty the government of India on its part has breached the trust embedded in the temporary instrument of accession. India cannot trade a natural resource of Kashmir with Pakistan, or vice versa. Pakistan has corresponding trust obligations to help the people in opposing India in her efforts to exploit the natural resources of Kashmir. If Pakistan had played by the jurisprudence of UN Resolutions on Kashmir and had not turned cold on the merits of Kashmir case over the past many years, India would have been restrained from day one. Waters of Kashmir are a natural resource embedded in the disputed habitat of Jammu and Kashmir. Under UN Resolutions these are Trust Properties and India has no legal claim over these waters It is time that the people of Kashmir should be helped by the Government of Pakistan in highlighting the manner in which India has exploited these natural resources (Waters) against the wishes of the people of Kashmir and how India has failed to hand over all Water Projects to Jammu and Kashmir Government. I have chaired a Working Group meeting in Delhi in 2004. It was attended among others by Abdul Rashid Shaheen MP National Conference, CPI (M) MLA Mohammed Yousuf Tarigami and other distinguished participants. After a rigorous debate it was resolved that Waters of Kashmir are a Trust Property embedded as a natural resource in the Disputed Habitat. Water resources in the natural habitat of Kashmir need to be defended as an integral part of self-determination. Dr Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

First International Offer to Resolve the Kashmir Dispute

On January 1, 1948, India formally referred the Kashmir issue to the United Nations underArticle 35 of the UN Charter. However, prior to this, on November 22, 1947, the PrimeMinister of the United Kingdom made a significant proposal to the Prime Minister ofPakistan, with a copy sent to the Prime Minister of India. In his proposal, the British Prime Minister inquired whether there was any way the UK couldassist in finding a solution to the complex problems arising from the evolving situation inKashmir. The communication highlighted a mutual understanding between the Indian andPakistani governments that consulting the people of Kashmir was essential for deciding thefinal accession of the region to either Pakistan or India. In his telegram dated November 22, 1947, addressed to the Prime Minister of Pakistan andcopied to the Prime Minister of India, the British Prime Minister noted: “Although the approach of your Government and that of the Indian Government is different,there seems to be agreement on both sides that a reference to the people of Kashmir is theright way to obtain a decision on the question of final accession to Pakistan or India.However, it is hardly practicable to take this step before the spring. Mr. Nehru suggested inhis broadcast of November 2, a referendum under international auspices like the UnitedNations, and you also suggested in your statement of November 16 that the United Nationsmight be asked to appoint representatives to assist in the settlement of the Kashmir problem.” The British Prime Minister further proposed: “Would you like me to take private soundings from the President of the International Court ofJustice to find out whether he is of the opinion that it would be practicable and if he would bewilling to try to get together a small team of international experts, not connected with India,Pakistan, or the United Kingdom, in the event of a joint request being preferred by theGovernments of India and Pakistan for this to be done.” He emphasized the potential benefits of involving independent persons to oversee theconsultation process, suggesting that: “I can see great advantages, if it proved practicable, for the machinery for consulting thepeople of Kashmir to be devised and administered under the supervision of independentpersons acting at the request of, and on behalf of, the two Governments jointly. After fullconsideration, I am inclined to think that the speediest and most satisfactory way of puttingthis idea into practice would be to have recourse to one special organ of the United Nations,namely, the International Court of Justice.” This early initiative by the United Kingdom underscored the international community’sinterest in facilitating a peaceful resolution to the Kashmir dispute through a process thatinvolved the will of the Kashmiri people and the expertise of international legal authorities. Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

Azad Kashmir – A Foreign Territory

Attorney General Munawar Iqbal Duggal argued in the Islamabad High Court case of Kashmiripoet Ahmad Farhad that Pakistani courts have historically treated Azad Kashmir as a foreignterritory in their judgments. This stance is consistent with past practices. Pakistan’s presence inAzad Kashmir is primarily to fulfill its responsibilities under the UNCIP Resolutions. While this argument holds legally, the political and administrative treatment of Azad Kashmirhas been markedly different and unjust. The Karachi Agreement’s Clause VIII is often used asa tool for ruling and administering Azad Kashmir. There is significant external interference,especially in the appointment of members to the superior judiciary in Azad Kashmir, whereindividuals from outside the state have maintained constitutional authority. The Azad Jammu and Kashmir Interim Constitution Act of 1974, formulated by Pakistan’sMinistry of Kashmir Affairs, functions more as a dictate and a form of modern colonialenforcement. This act contradicts the type of government and administration envisioned in theUNCIP resolutions. Azad Kashmir – Local Authority under the UN Template Under the UN template, Azad Kashmir is recognized as a Local Authority and should be underUN supervision. In the absence of such supervision, Pakistan has assumed responsibilitiesunder the UNCIP Resolutions to assist the Local Authority in improving administration andprogressing towards a UN-supervised plebiscite. Consequently, the legal basis for Pakistan’spresence in Azad Kashmir differs significantly from that of India’s presence in other parts ofJammu and Kashmir. The current relationship between the Government of Pakistan and the Government of AzadJammu and Kashmir (AJ&K) should align with the UN template. This relationship is intendedto be temporary, lasting only until the people of the state can participate in a UN-supervisedvote. However, there are well-argued views that AJ&K has failed to function effectively as aLocal Authority. The distribution of duties has been muddled by the Karachi Agreement ofApril 1949, the AJ&K Constitution Act of 1974, the AJ&K High Court decision of March1993, and routine directives from the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs. Much of this confusion is without merit and lacks legal sanction. These arrangements cannotoverride the stipulations of the UN template on Kashmir or the provisions outlined in Article257 of the Constitution of Pakistan. India’s Sphere of Influence The Government of India, during the 533rd meeting of the UN Security Council on March 1,1951, acknowledged that its authority over the Government of Kashmir is limited to certainsubjects, beyond which it can only offer advice without imposing decisions. It emphasized that“the people of Kashmir are not mere chattels to be disposed of according to a rigid formula;their future must be decided in their own interests and in accordance with their own desires.”The State Autonomy Committee Report of July 2000, adopted by both houses of the J & KLegislature, reminded the Government of India of its temporary and limited influence inJammu and Kashmir. At the 773rd meeting of the UN Security Council, the Philippines clarified the status of Jammuand Kashmir, stating that “pending the holding of a plebiscite, neither India nor Pakistan canclaim sovereignty over the State of Jammu and Kashmir.”

Clarifying the Jurisprudence of the Kashmir Case

As of May 28, 2024, the jurisprudence surrounding the Kashmir issue remains complex. TheIndian government’s actions on August 5, 2019, including the abrogation of Articles 370 and35-A, and the subsequent affirmation of these actions by the Indian Supreme Court, do notoverride Article 103 of the UN Charter. This article prioritizes obligations under the UNCharter over other international agreements, which includes the jurisprudence developed fromthe August 1947 Standstill Agreement with Pakistan and India’s acceptance of accession inOctober 1947. Article 1(2) of the UN Charter and UN Security Council Resolution 91 establish an estoppelagainst any actions by India or Pakistan that could prejudice the equality of the people ofKashmir, their right to self-determination, or the conduct of a free and fair plebiscite under UNsupervision. Despite the significant changes and confusion following India’s actions in 2019,the Indian Supreme Court’s decision, and rumors of Pakistan’s possible annexation of AzadKashmir, it is crucial to understand the limits and possibilities of Indian and Pakistani controlover the region. This understanding hinges on the historical title and the evolving jurisprudencein the field. The source of Indian and Pakistani administrative controls over Jammu and Kashmir lies in theUN framework. The jurisprudence of the Kashmir case has expanded beyond the interests ofthe people of Kashmir and the Government of Pakistan to include the international community.On October 31, 1947, the Prime Minister of India sent a telegram to the Prime Minister ofPakistan, stating: “Our assurance that we shall withdraw our troops from Kashmir as soon as peace and order arerestored and leave the decision regarding the future of this State to the people of the State isnot merely a pledge to your Government but also to the people of Kashmir and to the world.” This assurance remains a significant element of the jurisprudence in the field. Therefore, theKashmir issue encompasses both pre-UN and post-UN components of international law anddiplomatic assurances, emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of the situation as itstands today. Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com

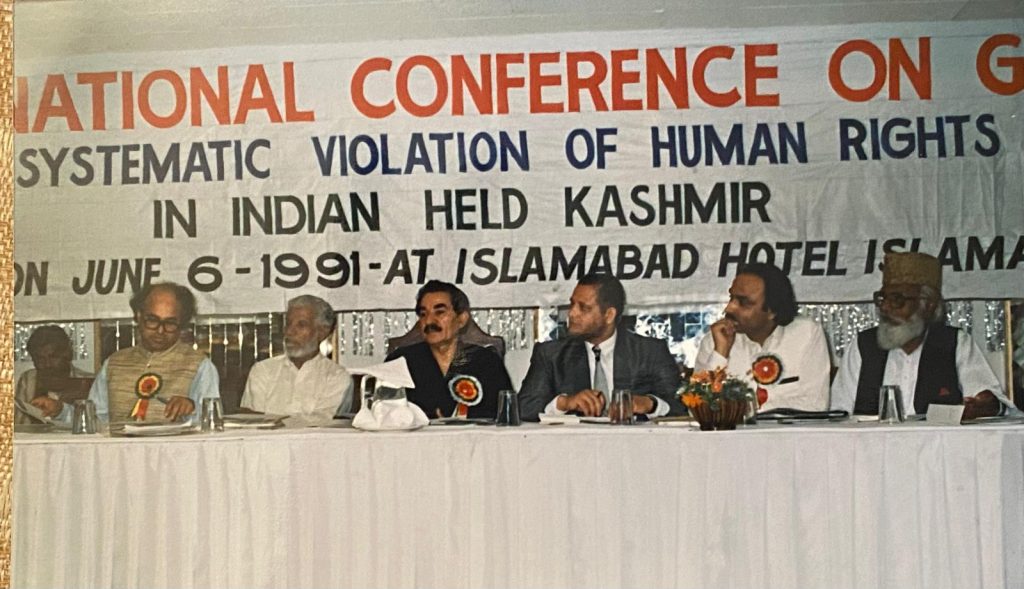

Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani

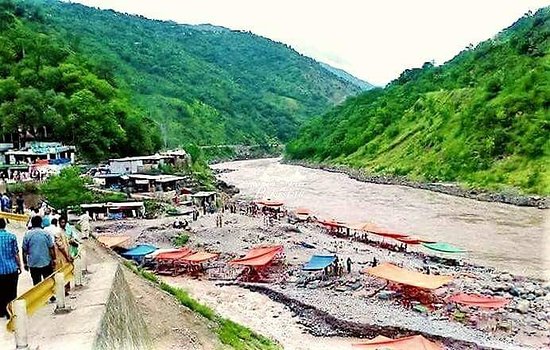

Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani hails from the historic village of Naranthal, also known as Jalsharee. The village sits on the banks of the river Jhelum. It is a modest geographical tributary of District Baramulla, Kashmir. Renowned for its Naranthal Temple and the refreshing Jalshree spring, the village shares its boundaries with two other villages Khadaniar (Khadniyar) and Drangbal, also known as Takisultan. The lineage of the Gilani family traces back to Baghdad, Iraq, journeying through Peshawar in British India and Lahore before settling in Khanyar, Srinagar, Kashmir, where they serve as Gaddi Nashin’s of the shrines of Dastgeer Sahib. Dr. Gilani’s educational journey traversed through the corridors of Government Middle School Khadniyar, Government Higher Secondary School Baramulla, and Degree College Baramulla. He pursued English Literature & Politics at the University of Kashmir, Law at S M Law College Karachi, Islamic Law at Kings College London, and International Law at Queen Mary University London. Additionally, his academic pursuits extended to Victimology at IUC Dubrovnik, in former Yugoslavia, and Peacekeeping/Humanitarian Operations & Election Monitoring in Pisa, Italy, under the 1996 UN and European Commission Programme. He stands as one of the select 40 individuals chosen under this esteemed program and holds a Ph.D. in the Jurisprudence of UN Resolutions and the Kashmir Case. His notable engagements include representing Unrepresented Peoples and Nations on the 33-member UN-NGO-Liaison Committee at the UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna (1993), where he also served on the UN-NGO Liaison Diplomatic Committee. Dr. Gilani addressed the Plenary and the Main Committee of the Conference, leaving an indelible mark with his insights. Begum Nusrat Bhutto from Pakistan and Atal Bihari Vajpayee from India, also addressed the Plenary and the Main Committee of the Conference on behalf of their respective countries. Dr. Gilani authored a chapter on Juvenile Justice in Saudi Arabia for a seminal work titled “Delinquency and Juvenile Justice in the Non-Western World,” providing invaluable insights for students, scholars, and practitioners. Acknowledged by the United Nations since January 1990, Dr. Gilani has lent his expertise to various international platforms, including the UN Commission for Human Rights, UN Sub Commission for Human Rights, UN Human Rights Council, Islamic Summit in Casablanca, and CHOGM-93. His commitment to promoting and safeguarding human rights transcends borders, evidenced by his diverse professional engagements, including roles at the Ministry of Information Government of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan Red Cross, Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation, and the UNHCR/UKIAS Refugee Section in London. He became the first Muslim Director of Millan Asian Centre in London and was elected on the General Council of UKIAS. Dr. Gilani’s efforts have earned praise, notably from the President of Pakistan Mr. Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghari, who commended his relentless advocacy for the self-determination of the Kashmiri people. His work embodies a steadfast commitment to justice and humanitarian causes, earning him recognition as a distinguished OP-ED writer and a champion of human rights on the global stage. He has remained a strong supporter of a dialogue between India and Pakistan and continues to urge them to respect the UN template on Kashmir. In October 1996, Major General Alfanso Passolano, the Chief of UNMOGIP, received special clearance from the UN headquarters in New York to fly from Srinagar to Rawalpindi. He held a meeting with a 5-member delegation from JKCHR, headed by Dr. Gilani. This historic meeting lasted for over three hours, and delved deep into the complex dynamics of the Kashmir conflict. It was the first instance of such high-level engagement between UNMOGIP and representatives from either side of the ceasefire line in Kashmir. Dr. Gilani’s has campaigned for the independence of judges and lawyers in Pakistan and Azad Kashmir during the lawyer’s movement in Pakistan. He has represented Benazir Bhutto, Asif Ali Zardari, Nawaz Shari, Shahbaz Sharif, Yousuf Raza Gilani and many other politicians at the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva. Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani has been a member of the International Platform of Jurists for East Timor since 1984, making significant contributions to East Timor’s independence. He is also a dedicated advocate for the Palestinian cause and has actively defended the human rights of minorities in Iraq and Kashmir at the United Nations. Currently, Dr. Gilani serves as the President of the Jammu and Kashmir Council for Human Rights (JKCHR), a non-governmental organization with special consultative status at the United Nations. The UN Secretary-General has received over 60 papers from JKCHR, which have been released as UN General Assembly documents on Kashmir during the UN Human Rights Council sessions in Geneva. The NGO contends for the UN supervised vote on the future of Kashmir. His dedicated work on the four components of Rights Movement, namely, rights, dignity, security and self-determination of all the people of Jammu and Kashmir, remains a lead and a reliable reference. The Co-Chairman PPP Asif Ali Zardari nominated Dr. Syed Nazir Gilani on 12 April 2008 as the first person in the list of 12 other people to receive the “Tipperary International Peace Award” conferred posthumously on Shaheed Mohtarama Benazir Bhutto in a ceremony in Tipperary, Ireland on Friday April 25, 2008. He has remained closely associated with three Bhutto’s – Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Nusrat Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto. Martial Law Government of General Zia ul Haq, booked him under Martial Law Regulations 13 and 53 for his advocacy of Kashmiri language and other published work. MLR 13 prescribed 5 years imprisonment and whipping up to 15 lashes and MLR 53 prescribed a death sentence. On 3 September 1982 Amnesty International cautioned Government of Pakistan that, “Should he be arrested on this charge, he would certainly be eligible for adoption as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.” Dr-nazirgilani@jkchr.com